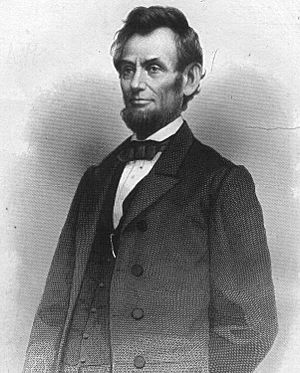

New research reveals a more emotional and troubled President Abraham Lincoln

Monday, February 21, 2005

As the bicentennial anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln's birth approaches in 2009, renewed interest is resulting in a new Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois in the United States of America – the town he called home.

Romance

Extrapolating out of a long-neglected set of interviews conducted by William Herndon, Lincoln's partner in law for 16 years, scholars have found that Lincoln seemed to have a soft side. Within a few years of his arrival, Lincoln fell in love with a local tavern keeper's daughter – Ann Rutledge. Herndon was surprised to hear about her, but of 24 people Herndon interviewed to who knew Lincoln and Ann at the time, 22 said he courted her. But in August, Rutledge contracted typhoid fever and died.

From then on, Lincoln would resemble the stoic man celebrated today. However, he was not without depression upon the death of his lover. One witness remembered, "He made a remark one day when it was raining that he could not bear the idea of its raining on her grave." Lincoln's exceptional reaction, to the point that many worried that he would commit suicide, had more to do with his own past – the death of his mother when he was but nine years old.

Lincoln would court again, this time to Mary Todd. After a guilty one year and still no commitment, Lincoln wrote to James Speed, a friend with whom he lived for more than four years, that he was racked with the "never-absent idea that there is one still unhappy whom I have contributed to make so. That still kills my soul." Upon a hasty marriage, "the debilitating episodes of 'hypo'"—as Lincoln called his depressions—"did not recur," and henceforth, Lincoln was known for his resolution, a matter of necessity to actually initiate and carry out the Civil War, and to emancipate the slaves.

Sexuality

In a his book, The Intimate World of Abraham Lincoln (ISBN 0743266390) (published posthumously), published last month, the late psychologist C.A. Tripp asserts that Abraham Lincoln was "predominately homosexual". Most historians, however, disagree, pointing out that Tripp is applying 20th century social mores to a 19th century context. They have noted that many men slept in beds together in the 19th century, and that Tripp is wrong when he states that Speed is the only one to whom Lincoln signed letters "Yours forever" – he signed notes to at least a dozen other people this exact way. Historian David Herbert Donald writes, "I simply cannot believe that, if the early relationship between Joshua Speed and Lincoln had been sexual, the president of the United States would so freely and publicly speak of it."

Early Politics

In his 20s and 30s, Lincoln was more subversive than people acknowledge. As a member of the Whig Party, he published anonymous letters in local newspapers deriding his party's political opponents, the Democrats. This practice was not uncommon at the time, but Burlingame, a historian who is writing a four-volume biography of Lincoln, has come across more than 200 such letters he believes were penned by Lincoln. During the presidential elections of 1836 and 1840, he accused the Democratic candidate, Martin Van Buren, of supporting black suffrage—what he seemed to suggest as an unforgivable sin.

However, through writing a mockery of the Democratic state auditor, James Shields, for being, "a fool as well as a liar," being challenged to a duel by Shields, and the two men barely being persuaded by their seconds to call it off, "Lincoln may, for the first time, have understood 'honor' and honorable behavior as all-important, as necessary, as a matter of life and death," writes Wilson.

Four years after his squabble with Shields, Lincoln was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. However, his 1846 two-year term was uneventful—he passed no bills and his only notable speech criticized the ongoing Mexican War, making him seem disloyal at home. Upon the elections of 1848 he merely went back home and got to work in his law practice. He was incredibly successful – he probably handled over 5,100 cases over his career – and earned perhaps twice the money historians previously thought. His supporters made him out a simple backwoods man, but Cullom Davis, professor emeritus at the University of Illinois–Sprinfield, commented that, "by the mid-1850s, you'd have to say he was enjoying an upper-middle-class lifestyle."

Again, he was a heroic man who would not only take clients whose cases he philosophically agreed with, Lincoln represented all people across all spectrums – from murderers to adulterers, farmers to doctors. In 1847, Lincoln even defended a Kentucky slave owner who wanted to keep some slaves in Illinois, where slavery was illegal. Lincoln lost.

Fortunately, Lincoln's large law practice gave him national recognition, and when push came to shove, despite being moralistically human, Lincoln tackled, head-on, the most vexing issue of at least one and one-half decades. The Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created future states such that voters could decide for themselves whether slaves would be allowed in their area, completely undermining the Missouri Compromise, gave Lincoln the inspiration he needed, along with an enduring and haunting image of shackled slaves on the Ohio River, "like so many fish upon a trot-line."

And so Lincoln leapt into the fray, denouncing slavery, although he undoubtedly found its guarantee entwined in the Constitution. Abraham Lincoln, however, would once again show his capacity to rise and meet the challenge; before leaving Illinois for the White House, he told a group of journalists, "Well, boys, your troubles are over now; mine have just begun."

Sources

- Justin Ewers. "The real Lincoln" — U.S. News & World Report, February 21, 2005

- Justin Ewers. "The Real Lincoln" — Ocnus.net, February 14, 2005