Scientists announce decoy-proof Ebola antibodies

Saturday, March 19, 2022

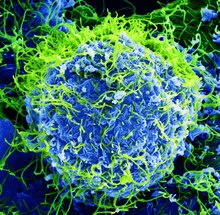

Image: User:BernbaumJG.

Findings published Thursday in Cell reveal the development of a new antibody treatment for the deadly disease caused by the Ebola virus and its relatives.

Scientists from the United States-based La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases identified two antibodies, 1C3 and 1C11, that can attack Zaire ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus.

There are currently no vaccines or antibody cocktails available to treat ebolaviruses other than Zaire ebolavirus. LJI President and CEO Erica Ollmann Saphire said: "Finding antibodies with this breadth is important because we don't know which virus in the genus of ebolaviruses is going to break out next."

Of the six ebolaviruses known to science, the Zaire and Sudan ebolaviruses are the two most deadly: the 2010s outbreak that killed eleven thousand was caused by the Zaire virus.

The new contribution made in this paper is that scientists used the imaging technique cryogenic electron microscopy to observe how and where the antibodies interact with the viruses.

The team saw that 1C3, instead of binding to the target site on the viral glycoprotein in the typical molecular lock-and-key fashion, stuck itself sideways across the glycoprotein, blocking three binding sites at once. Antibodies work by binding to pathogens and neutralizing their antigens.

1C11 works by interfering with the molecules that the virus would use to enter a cell. Because the Zaire and Sudan ebolaviruses use very similar mechanisms, 1C11 is effective against both.

According to the research team, the primary advantage that these two antibodies have over others is that they are resistant to cross-reactivity. When some viruses enter the body, including the Zaire and Sudan ebolaviruses, they produce excess glycoprotein and release it into the area like a smokescreen. This causes many of the body's antibodies bind to this glycoprotein instead, as many as 90 percent of them. 1C3 and 1C11 do not; they bind only to the real virus.

This means that antibody treatments based on 1C3 and 1C11 are likely to be effective at much lower doses than other treatments, as early experiments have already shown: One treatment has already been tested in non-human primates, and even the lowest doses used were 100 percent effective. This also means the human treatment might be much cheaper to produce than expected.

According to LJI, treatment based on these two antibodies would offer two advantages over existing treatments. First, patients with undiagnosed species of Ebolavirus can be treated with an antibody cocktail that is effective against more than one virus. Because doctors don't always have time to figure out which virus a patient has, this could save many lives. Second, these antibodies would be effective in patients with later stages of the disease.

The experiments were conducted using samples donated to Emory University by two Ebola survivors.

Sources

- "Ebola Virus Antibodies Offer Protection from Infection in Nonhuman Primates" — Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News, March 18, 2022

- B. David Zarley. "New Ebola antibodies neutralize the most dangerous strains of the virus" — Freethink, March 18, 2022

- "What is Ebola Virus Disease?" — Centers for Disease Control, March 18, 2022 (date of access)

- Jacob C. Milligan, Carl W. Davis, Xiaoying Yu, Philipp A. Ilinykh, Kai Huang, Peter J. Halfmann, Robert W. Cross, Viktoriya Borisevich, Krystle N. Agans, Joan B. Geisbert, Chakravarthy Chennareddy, Arthur J. Goff, Ashley E. Piper, Sean Hui, Kelly C.L. Shaffer, Tierra Buck, Megan L. Heinrich, Luis M. Branco, Ian Crozier, Michael R. Holbrook, Jens H. Kuhn, Yoshihiro Kawaoka, Pamela J. Glass, Alexander Bukreyev, Thomas W. Geisbert, Gabriella Worwa, Rafi Ahmed, Erica Ollmann Saphire. "Asymmetric and non-stoichiometric glycoprotein recognition by two distinct antibodies results in broad protection against ebolaviruses" — Cell, March 17, 2022

- La Jolla Institute for Immunology. "Promising antibody cocktail takes on Ebola virus—and its deadly cousin" — Eurekalert, March 17, 2022